Childhood Leukemia

Diagnosis

If CML is suspected, it is extremely important that your child be evaluated and treated at a major pediatric medical center that uses a certified central laboratory to identify any mutations or chromosomal abnormalities in the cancer cells. Accurate identification of changes in the cancer cells determines the diagnosis and best treatment.

To diagnose CML, your child’s pediatric oncologist will first obtain a complete medical history, do a thorough physical exam, and order many tests, including:

- A complete blood count, including:

- The number and type of WBCs

- The number of RBCs and platelets

- The portion of the blood sample made up of RBCs (hematocrit)

- Additional blood tests (e.g., blood chemistries and evaluation of liver and kidney function)

- Bone marrow aspiration or biopsy to evaluate the cancer cells and confirm the diagnosis

- Genetic studies on the cancer cells

These procedures and tests are described in Chapter 9, Coping with Procedures and Appendix A, Blood Tests and What They Mean.

My daughter, Dana, was 9 years old when she had a stomachache that began in the middle of a soccer tournament. We took her to the doctor who examined her and ordered some routine blood work. They called us that day to say her white blood cell count was 65,000 and that she needed to come in right away for more tests. After the results came back, the doctor said that Dana probably had leukemia. Dana later told me, “Dad, that’s the first time I’ve ever seen you cry.” They started her on Gleevec®, we got another opinion from an expert across the country, then we just tried to make life as normal as possible. Fast forward 11 years, and Dana is in college, playing on the college soccer team, volunteers at the college radio station as a DJ, and is still taking Gleevec® every evening.

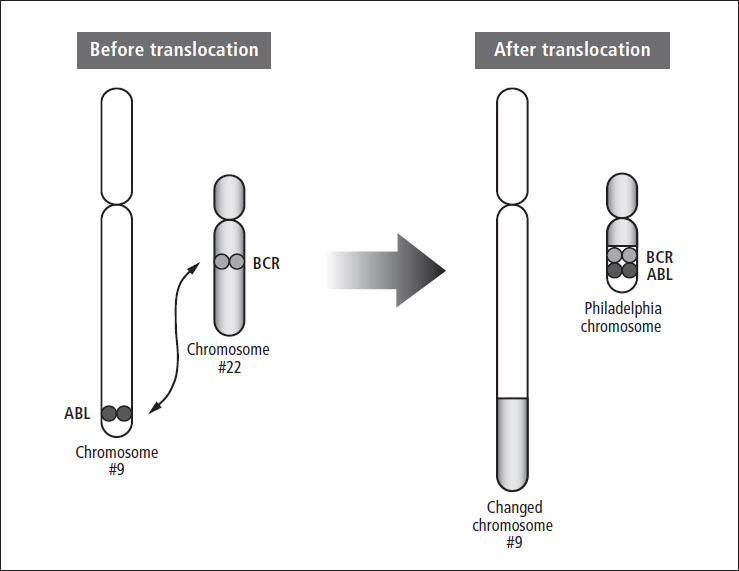

In more than 90% of children with CML, analysis of cancer cells shows a genetic abnormality called the Philadelphia chromosome (see Figure 6–2). This chromosome contains a translocation (or swap) of genetic material involving chromosomes 9 and 22, called t(9;22). This rearrangement creates a new gene (called BCR-ABL) that codes for a protein that causes the cancerous cells to rapidly reproduce. These chromosome changes are not inherited from a parent—they happen during a person’s lifetime.

Figure 6–2: The Philadelphia chromosome

CML has three phases: 1) chronic phase, 2) accelerated phase, and 3) blast phase. The following table shows how your child’s doctor will determine the phase of the disease.

Chronic Phase |

Accelerated Phase |

Blast Phase |

Documented t(9;22) or BCR-ABL fusion gene |

Peripheral blood or bone marrow has 15% to 19% blasts |

Blasts in peripheral blood or bone marrow >20% |

Blasts in bone marrow <15% |

Persistent low platelet count (<100,000) that is unrelated to therapy |

Blast accumulation in organs other than the spleen |

Does not meet any criteria for accelerated or blast phase |

Increasing spleen size and WBC count despite treatment |

Clusters of blasts found in bone marrow biopsy |

Approximately 95% of children with CML are diagnosed in the chronic phase. If untreated, the chronic phase usually lasts about three to five years. With current treatments, the majority of children remain in remission for many years.

My son was 3 years old when he was diagnosed with CML. We noticed that his abdomen was distended—sometimes it was hard and sometimes it was soft. First we were told it was constipation. Then we went to another doctor for an unrelated medical issue. He was concerned and ordered an ultrasound, which showed a very enlarged spleen and kidneys. They called and asked us to come back in for blood work the next day. So we went back in for that. That same night, after our son was asleep, they called and said to go to the children’s hospital immediately because his white blood cell count was over 300,000.

Table of Contents

All Guides- Introduction

- 1. Diagnosis

- 2. Overview of Childhood Leukemia

- 3. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

- 4. Acute Myeloid Leukemia

- 5. Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia

- 6. Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia

- 7. Telling Your Child and Others

- 8. Choosing a Treatment

- 9. Coping with Procedures

- 10. Forming a Partnership with the Medical Team

- 11. Hospitalization

- 12. Central Venous Catheters

- 13. Chemotherapy and Other Medications

- 14. Common Side Effects of Treatment

- 15. Radiation Therapy

- 16. Stem Cell Transplantation

- 17. Siblings

- 18. Family and Friends

- 19. Communication and Behavior

- 20. School

- 21. Sources of Support

- 22. Nutrition

- 23. Insurance, Record-keeping, and Financial Assistance

- 24. End of Treatment and Beyond

- 25. Relapse

- 26. Death and Bereavement

- Appendix A. Blood Tests and What They Mean

- Appendix B. Resource Organizations

- Appendix C. Books, Websites, and Support Groups