Childhood Leukemia

Basic Genetics

Treatment for childhood leukemia is increasingly based on genetic changes that are found in cancer cells. Therefore, having a basic knowledge of genetics will help you understand some of the terms healthcare providers may use when discussing your child’s type of leukemia and proposed treatment.

Our bodies are made of cells, trillions of them. Each of these cells carries all the information the cells need to reproduce and keep our bodies functioning. Inside the nucleus of every cell are chromosomes, which contain genes that provide the instructions the body needs to live and to pass certain traits from a parent to a child. Genes are composed of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), which comes in strands that resemble a twisted ladder (see Figure 2–2).

Figure 2–2: Cells, chromosomes, and DNA

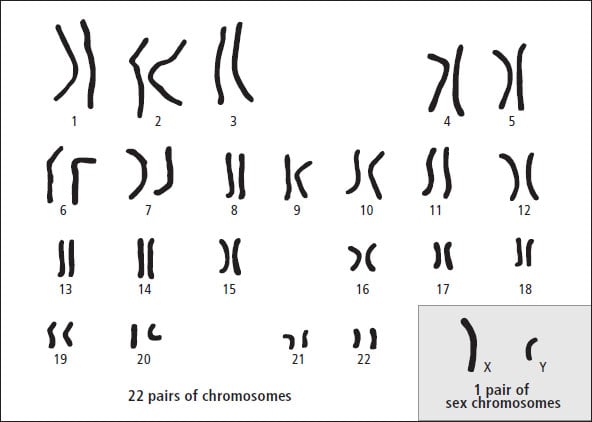

Chromosomes come in pairs, and a normal human cell contains 46 chromosomes (see Figure 2–3). Of these, 44 are the same in males and females, but one pair (called sex chromosomes) is different. Females have two X chromosomes in that pair, and males have one X and one Y chromosome. In some types of childhood leukemia, the cancer cells contain too many or too few chromosomes.

Figure 2–3: The 23 pairs of chromosomes

The cancer cells in children with leukemia often contain mutations, which are permanent changes in a gene’s DNA. Genetic changes happen all the time in our cells, but the body possesses sophisticated tools for detecting and repairing the changes. A change only becomes a mutation when a repair cannot be made or is made incorrectly. These mutations come in four main varieties:

- Duplications: When some genes are repeated on the chromosome

- Deletions: When part of a chromosome is lost

- Translocations: When there is a break in the DNA and some genes from one chromosome attach to a different chromosome

- Inversions: When two breaks occur and a segment reattaches backwards, which reverses the sequence of genes

Scientists have identified many mutations in leukemia cells. Some of these mutations are associated with development of the disease. Others predict which therapies will be most effective for a particular child or how the child will react to certain drugs. For these reasons, when a child is diagnosed with leukemia, doctors immediately order numerous genetic tests on the cancer cells to gather all information possible about how the child should be treated and how she is likely to respond to treatment. This genetic knowledge has greatly improved doctors’ ability to identify the best treatment for each child diagnosed with leukemia. Researchers continue to look for new genetic mutations, so you may be asked to allow an extra portion of the diagnostic marrow to be saved for research.

Table of Contents

All Guides- Introduction

- 1. Diagnosis

- 2. Overview of Childhood Leukemia

- 3. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

- 4. Acute Myeloid Leukemia

- 5. Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia

- 6. Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia

- 7. Telling Your Child and Others

- 8. Choosing a Treatment

- 9. Coping with Procedures

- 10. Forming a Partnership with the Medical Team

- 11. Hospitalization

- 12. Central Venous Catheters

- 13. Chemotherapy and Other Medications

- 14. Common Side Effects of Treatment

- 15. Radiation Therapy

- 16. Stem Cell Transplantation

- 17. Siblings

- 18. Family and Friends

- 19. Communication and Behavior

- 20. School

- 21. Sources of Support

- 22. Nutrition

- 23. Insurance, Record-keeping, and Financial Assistance

- 24. End of Treatment and Beyond

- 25. Relapse

- 26. Death and Bereavement

- Appendix A. Blood Tests and What They Mean

- Appendix B. Resource Organizations

- Appendix C. Books, Websites, and Support Groups