Childhood Leukemia

Subcutaneous Port

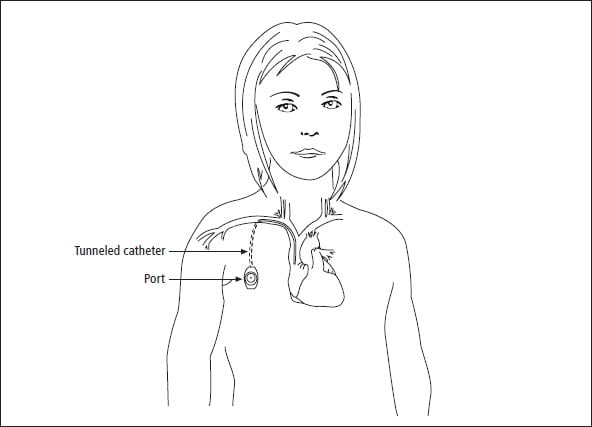

Several types of subcutaneous (under the skin) ports are available. The subcutaneous port differs from the external catheter in that it is completely under the skin. A small metal chamber with a rubber top is implanted under the skin of the chest. A catheter threads from the metal chamber (portal) under the skin to a large vein near the collarbone, and then inside the vein to the right atrium of the heart (see Figures 12-2 and 12-3). Whenever the catheter is needed for a blood draw or an infusion, a needle is inserted by a nurse through the skin and into the rubber top of the portal. Usually a topical numbing agent such as EMLA® is used to make the needle insertion less painful.

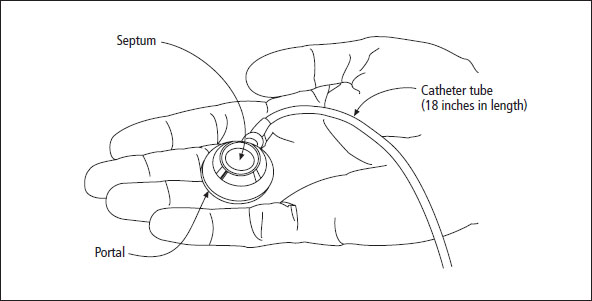

Figure 12–2: Parts of the subcutaneous port

How it’s put in

The subcutaneous port is implanted under general anesthesia; the procedure generally takes less than an hour. The surgeon or interventional radiologist makes two small incisions: one in the chest where the port will be placed, and the other near the collarbone where the catheter will enter a vein in the lower part of the neck. First, one end of the catheter is placed in the large blood vessel of the neck and threaded into the right atrium of the heart. The other end of the catheter is tunneled under the skin where it is attached to the portal. Fluid is injected into the portal to ensure the device works properly. The portal is then placed under the skin of the chest and stitched to the underlying muscle. Both incisions are then stitched closed. The only evidence that a catheter has been implanted are two small scars and a bump under the skin where the portal rests.

Christine had her port surgery late at night. The resident gave her some premedication, then the chief resident ordered him to give her more. She felt so silly that she looked at me, giggled, and said, “Mommy has a nose as long as an elephant’s.” I asked the surgeon if I could be in the recovery room when she awoke, and he said, “Sure.”

Figure 12–3: Subcutaneous port

How it works

Because the entire subcutaneous port is under the skin, a needle is used to access it. The skin is thoroughly cleansed with antiseptic, and then a special needle is inserted through the skin and the rubber top of the portal. The needle is attached to a short length of tubing that hangs down the front of the chest. A topical anesthetic cream can be applied one hour before the needle poke to anesthetize the skin (see Chapter 9, Coping with Procedures). Subcutaneous ports have a rubber top (septum) that reseals after the needle is removed. It is designed to withstand years of needle insertions, as long as a special “non-coring” needle is used each time.

If your child is in a part of treatment that requires using the line every day, the nurse will attach the tubing to IV fluids or will close the end off with a sterile cap after flushing the line with saline solution. A transparent dressing will be put over the site where the needle enters the port. The port can remain accessed in this way for up to seven days. After that time, to avoid the risk of infection, the needle should be removed and the port reaccessed when necessary. If the needle and tubing are to be left in place, it is important to tape them securely to the chest to avoid accidents.

Molly (3 years old) hated tape removal, so we did not secure the IV tubing to her stomach or chest. On one of her many trips to the potty, we accidentally tugged on the tubing and caused a very small tear in the skin around the needle. It became infected. We did home antibiotics on the pump and felt very fortunate that we were able to clear the line with antibiotics. We were glad our doctor was not too quick to remove the line, but it did require two weeks off chemotherapy.

Care of the port

The entire port and catheter are under the skin, so no daily care is required. After insertion, once the skin over the port heals it can be washed just like the rest of the body. Frequent visual inspections are needed to check for signs of infection, including redness, swelling, pain, drainage, or warmth around the port. Fever, chills, tiredness, and dizziness may also indicate that the line is infected. You should notify the doctor immediately if any of these signs are present or if your child has a fever above 101° F (38.5° C).

My son had a PORT-A-CATH® for 3 years, from age 14 to 17. During that time, he played basketball, football, softball, and threw the shot put in track. His port was placed on his left side just below his armpit. For football, I worked with the trainer and we developed a special pad that went into a pocket I sewed into some T-shirts. That way the port had a little extra padding. We also found shoulder pads that had a sidepiece that covered the area. He never had any problems or soreness from the port.

The subcutaneous port must be accessed and flushed with heparin at least once every 30 days, which might coincide with clinic visits or blood draws. Ports don’t require maintenance by a parent.

Nico completely flips out when his port is accessed now (since a really bad experience in-patient). So the child life specialist always comes in and tries to help and offer suggestions. Today she said something that reminded me of a book that I absolutely love called Happiest Toddler on the Block. The basic idea is that you validate their feelings by repeating their feelings, and if you do this enough, they calm down. For example, to calm Nico who was hitting, kicking, and screaming after the port access, the child life specialist said, “Nico is really mad.” She said it several times and eventually he just stopped screaming/crying. Then he started yelling that he wanted to go home and she just said, “I bet you really do want to go home.” He calmed down to this whereas my “We can go home later” was only making him more upset. The book basically explains that if kids (or really anyone) does not feel that their feelings are recognized, they will escalate behaviors that communicate the feelings.

Risks

The risks for a subcutaneous port are similar to those for an external catheter: infection, clots, and, rarely, kinks or rupture. If the needle is not properly inserted through the rubber septum, or if the wrong kind of needle is used, fluids can leak into the tissue around the portal.

Brent (8 years old) has had a PORT-A-CATH® for 33 months with absolutely no problems. He uses EMLA® to anesthetize it prior to accessing. He hates finger pokes so much that he has his port accessed every time he needs blood drawn.

Infection. Most studies show that the infection rate for subcutaneous ports is lower than that of external catheters. If the subcutaneous port does become infected, it is treated the same way an infected external catheter is treated.

When my daughter had a line infection, I wanted to use the antibiotic pump at home. It was hard, though. It took two hours per dose, three doses per day, for 14 days. I would get up at 5 a.m. to hook her up, so that she would sleep through the first dose. The second dose I would give while she watched a TV show in the early afternoon. Then I would hook her up at bedtime so she would sleep through it. I had to wait up to flush and disconnect, so I was very tired by the end of the two weeks.

Kinks, clots, and ruptures. These events rarely occur with a subcutaneous port. If they do occur, they are treated as described in the external catheter section.

When we got to the clinic for weekly chemo, no matter what gravity-defying positions we tried (raising arms, lying down, standing up), our nurse couldn’t get the line to flush. The port was clogged. Luckily, they were able to clear the line with an injection of streptokinase, although it meant entertaining her in the clinic for more than an hour while we waited for it to work. They did tell us that if this didn’t work we’d have to go in overnight for slow infusion of chemo, but the line cleared, and we did chemo outpatient.

Table of Contents

All Guides- Introduction

- 1. Diagnosis

- 2. Overview of Childhood Leukemia

- 3. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

- 4. Acute Myeloid Leukemia

- 5. Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia

- 6. Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia

- 7. Telling Your Child and Others

- 8. Choosing a Treatment

- 9. Coping with Procedures

- 10. Forming a Partnership with the Medical Team

- 11. Hospitalization

- 12. Central Venous Catheters

- 13. Chemotherapy and Other Medications

- 14. Common Side Effects of Treatment

- 15. Radiation Therapy

- 16. Stem Cell Transplantation

- 17. Siblings

- 18. Family and Friends

- 19. Communication and Behavior

- 20. School

- 21. Sources of Support

- 22. Nutrition

- 23. Insurance, Record-keeping, and Financial Assistance

- 24. End of Treatment and Beyond

- 25. Relapse

- 26. Death and Bereavement

- Appendix A. Blood Tests and What They Mean

- Appendix B. Resource Organizations

- Appendix C. Books, Websites, and Support Groups