Childhood Leukemia

Treatment

Treatment for children with ALL is complicated and lasts for years. It involves chemotherapy and sometimes radiation, stem cell transplantation, or immunotherapy. Below are a few issues that apply to treatment of all types of ALL.

- Adolescents: Teenagers and young adults do better when they are treated on pediatric protocols at large children’s hospitals, rather than on adult protocols at local or even large hospitals.

- CNS disease: Few children have detectable disease in their CNS at diagnosis, but most children develop disease in the brain and spinal cord if preventive chemotherapy is not delivered to the brain. Therefore, treatment for children with ALL includes chemotherapy injected into the CSF during spinal taps (called intrathecal chemotherapy). Use of radiation to the brain to prevent CNS disease has been dramatically reduced in recent years.

- Disease in the testes: Around 2% of boys are found to have disease in their testes at diagnosis. Treatment may or may not include radiation to the testes.

- Compliance affects cures: Treatment for ALL lasts for years. Studies have shown that children who are routinely not given their oral medications on schedule have higher rates of relapse. This doesn’t mean you should worry if you miss a few doses or if your child throws up a few doses. That happens to all families. The children at risk are those who routinely don’t get the prescribed oral or liquid medications at home; this is particularly a problem with adolescents. Your child’s treatment team should closely monitor compliance with taking medications at home and provide help to families who are having difficulties.

- Pharmacogenetics: Blood tests are available to assess children’s genetically determined ability to metabolize some medications. These tests are discussed in Chapter 13, Chemotherapy and Other Medications. If children break down certain drugs slower than normal, the drug levels can build up in their bodies, resulting in increased toxicity and risk of infection. So all children who develop severe toxicities during treatment (severe infections, very low WBC counts, or high results on liver function tests) should have pharmacogenetic testing. Some institutions test children with ALL before beginning treatment.

-

Remission: Most children with ALL are in remission (less than 5% leukemic blasts in the bone marrow) at the end of the induction phase. Children and teens not in remission by day 29 (e.g., 10% blasts in the bone marrow) are usually reclassified as very high-risk and are given intensified chemotherapy. Remission is not related to MRD. Results of MRD testing are used to determine risk level. Here are three examples:

- A child with less than 5% blasts and less than 0.01 MRD on day 29 is in remission and would not have his risk level increased.

- A child with less than 5% blasts and 0.2 MRD on day 29 is in remission but would require more intense treatment (risk level would increase).

- A child with 10% blasts in the bone marrow on day 29 is not in remission and would require more intense treatment (risk level would increase).

Although the goal of treatment is to eliminate all cancer cells, there are many more cancer cells left after the induction phase of treatment. One pediatric oncologist explains as follows.

Remission is defined as less than 5% blasts in the bone marrow. I always tell parents that friends and family may ask why chemo is still necessary if the child is in remission. I explain that MRD of zero does not mean zero cancer in the body. It means we’ve reached the lowest level of detection with current technology, but we can’t stop therapy. MRD is primarily used by physicians to risk-stratify patients so they get the treatment they need and no more.

The rest of this chapter contains brief descriptions of the standard ALL treatments (not clinical trial treatments) used in 2017 for children. It is divided into five sections: B-cell ALL, T-cell ALL, Ph+ ALL, infant ALL, and children with Down syndrome and ALL. Keep in mind that different institutions offer different treatments in different phases, so what follows is a general outline of the most commonly used treatments. In addition, risk level can change depending on response to treatment, so children with lower-risk disease can have phases deleted and children with higher-risk disease may be given more intensive treatment. All children with ALL receive treatment to prevent the spread of the disease to the CNS (brain and spinal cord).

Your child’s pediatric oncologist will give you several documents. One is an overall plan that shows the phases of therapy. The other is called a roadmap, which clearly describes the treatment your child will receive during each specific phase. If your child is enrolled in a clinical trial, a lengthy document that covers all aspects of the protocol is also available for parents (see Chapter 8, Choosing a Treatment).

All treatment protocols have phases where blood counts will be very low and the risk of life-threatening infection is high. You can expect to have your child hospitalized during these phases.

B-cell ALL

Based on criteria described earlier in this chapter, children with B-cell ALL are classified as low risk, average risk, high risk, or very high risk. The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) classifies the following children and teens with B-ALL as very high risk:

- All teenagers and young adults (ages 13 to 25)

- Infants younger than 1, especially those with an MLL gene rearrangement

- Children or teens with certain genetic abnormalities, very low number of chromosomes (<44), the Philadelphia chromosome, or the translocation called t(17;19)

- Children with high MRD levels at the end of induction (4 weeks) or a later time (e.g., 12 weeks)

The reports we received were: molecular diagnostics, cytogenetics, and surface markers. The reports showed that Tom had B-cell ALL with high hyperdiploidy and the presence of the triple trisomy 4, 10, 17, but without any translocations. The fact that he had the triple trisomy was supposed to carry a good prognosis. However, he was still MRD+ at the end of induction and consolidation.

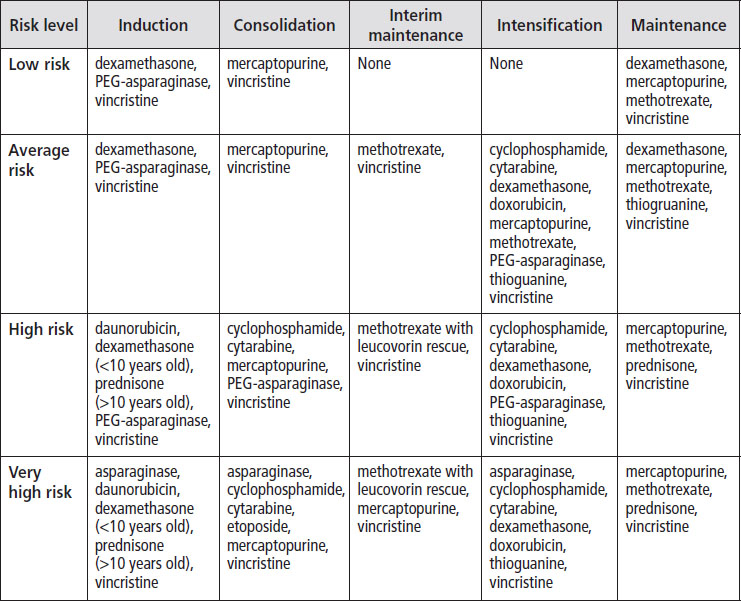

The following table shows the phases of treatment and the drugs most commonly used during each phase.

Asparaginase reactions. Some children have reactions to PEG-asparaginase, and in these cases, they are usually given a related medication called Erwinia L-asparaginase for the rest of treatment. Children who have severe reactions (e.g., grade 3 or 4 pancreatitis) usually don’t receive any more of this drug.

Protecting the heart. Because daunorubicin and doxorubicin can cause heart damage, some protocols include the drug dexrazoxane. This drug has been shown to protect the heart in some treatment protocols, and in some it has not been tested.

Testes. Boys who have testicular disease at diagnosis may need a testicular biopsy at the end of induction. If the biopsy shows disease, boys may receive testicular radiation during the consolidation phase.

Stem cell transplantation. Children with very high risk disease and fewer than 44 chromosomes in their cancer cells are sometimes offered a stem cell transplant after consolidation if a matched donor is available.

CNS treatment. Intrathecal chemotherapy (injected into the spinal fluid during a spinal tap) is used to prevent spread of disease to the brain for all children with B-cell ALL, with schedules depending on risk category. The chemotherapy drugs given are:

- IT methotrexate, cytarabine, and hydrocortisone (called “triples”);

- IT cytarabine; or

- IT methotrexate

Cranial radiation. This is no longer used for newly diagnosed children at low, average, or high risk. Use of cranial radiation to treat children and teens with very-high-risk B-cell ALL varies among institutions and research groups. Some institutions increase systemic chemotherapy for very-high-risk children and use no cranial radiation for any children with B-cell ALL; others use cranial radiation for certain groups of children at very high risk of relapse. Children who are sometimes treated with both intrathecal medication and cranial radiation include those with:

- CNS3 disease at diagnosis (5 or more blasts in CNS fluid)

- Extremely high WBC counts at diagnosis

- Certain very-high-risk genetic characteristics of the cancer cells

My 2-year-old son was diagnosed with B-cell ALL with the MLL rearrangement and CNS3 disease. During induction, he developed grade 3 pancreatitis after the second dose of asparaginase and was very ill. So, he was not given any more asparaginase. Because he had disease in his CNS at diagnosis, he also had 1,200 cGy of cranial radiation. He was one of the few kids we knew who sailed through induction and felt good most of the time (except for the pancreatitis).

T-cell ALL

T-cell ALL occurs most often in older boys and adolescents. These children often have high WBC counts (>100,000 μL) and masses in their chests (called mediastinal masses) at diagnosis. The presence of a mediastinal mass is a medical emergency, as it can press on the trachea (windpipe), causing coughing or shortness of breath. Such children will be admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit for initial evaluation and therapy. With T-cell ALL, the thymus gland in the neck may also be affected.

Our daughter Maya was not feeling well the week before her 5th birthday. During her birthday party, we noticed she was breathing shallowly. The next day she looked pale and her face was puffy, so my husband took her to urgent care. They took vitals and listened to her lungs and within two minutes the doctor said, “Drive straight to the ER or we’ll call an ambulance.” At the ER, they did an x-ray that showed a large mass in her chest that had collapsed one of her lungs. In the ICU, they tried to sedate her to put in a chest tube and to do a bone marrow aspiration, spinal tap, and PICC line, but she crashed. At one point, there were 20 to 30 people in the room. They did most of those tests with local anesthesia instead of sedation. At this point, Maya said, “Excuse me, I did not order this!” Diagnosis: T-cell ALL.

T-cell ALL used to carry a worse prognosis than B-cell ALL. But due to more intensive therapies, the remission rates are now almost identical. The COG standard treatment for children and teens with T-cell ALL is divided into standard risk, intermediate risk, and very high risk.

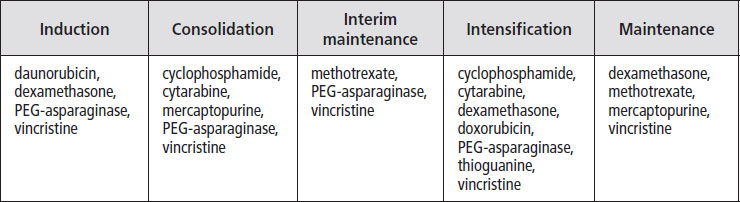

Treatment for children with standard- or intermediate-risk T-cell ALL usually includes five or six phases, as well as treatment to prevent spread of the disease to the brain. The table below shows the phases of treatment and the drugs most commonly used for children or teens at standard risk.

Children with intermediate-risk disease may have two intensification phases, and children with very high-risk disease may have three intensification phases of treatment. Children and teens not in remission by day 29 and with MRD of more than 0.01 are usually reclassified as very high risk and are given intensified chemotherapy.

Asparaginase reactions. If children react to PEG-asparaginase, they are usually given a related medication called Erwinia L-asparaginase for the rest of treatment. Children who have severe reactions (e.g., grade 3 or 4 pancreatitis) usually do not receive any more of this drug.

Protecting the heart. Because daunorubicin and doxorubicin can cause heart damage, some protocols include the drug dexrazoxane. This drug has been shown to protect the heart in some treatment protocols, and in some it has not been tested.

Testes. Boys who have testicular disease at diagnosis may need a testicular biopsy at the end of induction. If the biopsy shows disease, boys may receive testicular radiation during the consolidation phase.

CNS treatment. Intrathecal chemotherapy (injected into the spinal fluid during a spinal tap) is used for all children with T-cell ALL. The chemotherapy drugs given to prevent spread of disease to the brain are:

- IT cytarabine

- IT methotrexate with leucovorin rescue

Cranial radiation. Some institutions use cranial radiation (1,200 or 1,800 cGy) for children who have T-cell ALL with CNS disease at diagnosis. Other do not use cranial radiation unless a child has relapsed in the CNS. Whether or not to use cranial radiation in children with T-cell ALL is the subject of ongoing clinical trials.

Because our 5-year-old daughter had a mass in her chest at diagnosis, she had five days of steroids before beginning treatment for the T-cell ALL. The mass dramatically shrunk during the pretreatment with steroids. We signed up for a clinical trial and were randomized to the experimental arm (included bortezomib). She had a hard time during treatment—a double lung fungal infection, pseudomonas infections on her skin that required surgical removal, multiple delays of treatment, a year of physical therapy, and more. But, she’s almost finished maintenance so the end is in sight.

Philadelphia Chromosome ALL

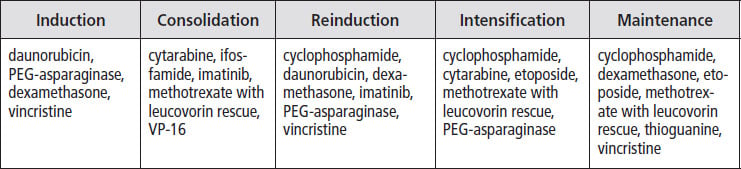

About 3% of children diagnosed with ALL are found to have the Philadelphia chromosome (called Ph+) in their cancer cells. It is more common in older children, teens, and young adults. In the past, this was a difficult type of leukemia to treat, but development of the targeted drug Gleevec® (imatinib) led to dramatic improvements in cure rates. Currently, treatment for children and teens with Ph+ ALL involves intensive chemotherapy and imatinib or a related medication. If imatinib stops working, a stem cell transplant from a matched donor (if available) is usually recommended. Different institutions treat this type of ALL in different ways. The table below shows the phases of treatment and drugs used by some institutions to treat children with Ph+ ALL.

Asparaginase reactions. Some children have reactions to PEG-asparaginase, and in these cases, they are usually given a related medication called Erwinia L-asparaginase for the rest of treatment. Children who have severe reactions (e.g., grade 3 or 4 pancreatitis) usually do not receive any more of this drug.

Protecting the heart. Because daunorubicin and doxorubicin can cause heart damage, some protocols include the drug dexrazoxane. This drug has been shown to protect the heart in some treatment protocols, and in some it has not been tested.

CNS treatment. Intrathecal chemotherapy (injected into the spinal fluid during a spinal tap) is used for all children with Ph+ ALL. The chemotherapy drugs given to prevent spread of disease to the brain are:

- IT cytarabine

- IT methotrexate with leucovorin rescue

Cranial radiation. Some institutions use cranial radiation (1,200 or 1,800 cGy) for children who have CNS disease at diagnosis. Others do not use cranial radiation unless a child has relapsed in the CNS.

Our treatment discussion left a lot to be desired. After we found out it was Ph+ ALL, we were offered two treatment plans—one with Gleevec®, which our hospital had never used, and a clinical trial with dasatinib, also something they had no experience with. We asked for information about both options, and were told they were so new there wasn’t any. When we asked how we could make a choice with no information, they said to make our best guess, and that we had 24 hours to do that. So, we started calling friends in the medical field and were connected to a person who had been involved in the initial Bristol Myers Squibb trials and he filled us in on those. We also contacted a cousin who had been on Gleevec® for years to treat his CML. We ended up enrolling in the trial, but it was mostly based on a leap of faith and anecdotal information that it did a better job of crossing the blood–brain barrier.

A recently discovered type of ALL is called Philadelphia chromosome-like ALL. Although the leukemia cells of children with this type of ALL do not contain the BCRABL gene, the leukemia cells are sometimes sensitive to targeted TKI drugs, just like Ph+ ALL is. Oncologists treat children with Philadelphia chromosome-like ALL with intensive chemotherapy as well as dasatinib.

Infant ALL

About 150 infants younger than 12 months old are diagnosed with ALL every year in the United States. These infants are very challenging to treat because they often:

- Are very ill at diagnosis

- Have very high WBC counts

- Have characteristics of their cancer cells (e.g., MLL rearrangement) that are especially hard to treat

- Are often slow to respond to treatment

- Develop severe treatment-related toxicities (e.g., infection) at a higher rate than do older children with ALL

Many types of treatment have been tried for infants with ALL. Sometimes newly diagnosed children with very high WBC counts and CNS symptoms have an exchange transfusion in which all of their blood is replaced with donor blood. Stem cell transplant is not more effective than conventional chemotherapy for infants. Risk groups for infants with ALL often change, but the most recent are:

- Standard risk: No MLL rearrangement

- Intermediate risk: MLL rearrangement and infant is at least 90 days old

- High risk: MLL rearrangement and infant is younger than 90 days old

In general, children with no MLL rearrangements are treated on protocols for high-risk ALL or even more intensive treatment. Recent protocols for infants with ALL were divided into five phases—induction, post induction, reinduction, consolidation, and continuation. The drugs used were some combination of asparaginase, cyclophosphamide (with mesna), cytarabine, daunorubicin, dexamethosone, etoposide, filgrastim, mercaptopurine, methotrexate with leucovorin rescue, prednisone, and vincristine. Schedules and doses varied by risk category. Research is ongoing to identify specific genetic characteristics so targeted therapies can be developed, and clinical trials are being developed to test these drugs.

Protecting the heart. Because daunorubicin and doxorubicin can cause heart damage, some protocols include the drug dexrazoxane. This drug has been shown to protect the heart in some treatment protocols, and in some it has not been tested.

Asparaginase reactions. Some children have reactions to PEG-asparaginase, and in these cases, they are usually given a related medication called Erwinia L-asparaginase for the rest of treatment. Children who have severe reactions (e.g., grade 3 or 4 pancreatitis) usually do not receive any more of this drug.

CNS treatment. Intrathecal chemotherapy (injected into the spinal fluid during a spinal tap) is used for all infants with ALL. The chemotherapy drugs given to prevent spread of disease to the brain are methotrexate, hydrocortisone, and cytarabine (called triple intrathecals).

Down syndrome and ALL

Approximately 2 to 3% of children with ALL also have Down syndrome. It has long been known that these children are very sensitive to chemotherapy drugs and very easily develop severe infections. Efforts have been made to decrease doses to minimize toxicity while still maintaining cure rates. Currently, there is no widely accepted standard treatment for children with Down syndrome and ALL. Below is the treatment given at COG institutions in 2017 for children with standard risk B-cell ALL and Down syndrome (children with Down syndrome are rarely diagnosed with T-cell ALL). Standard risk in B-cell ALL is defined as:

- Age 1 to 9

- WBC <50,000/μL

- No MLL rearrangement, hypodiploidy, or Philadelphia chromosome

- Day 29 bone marrow MRD <0.01

- No CNS3 or testicular leukemia at diagnosis

My 11-year-old daughter, who has Down syndrome, was visiting her dad who lives eight hours from us. She had an off and on fever as well as petechiae, so he took her to his physician, who diagnosed an ear infection and put her on antibiotics. He said if it didn’t improve perhaps she needed some blood work done. Then, a few days later, pus started coming out of her ear and her temperature rose to 104o. My ex took her to her former pediatrician, who took one look at the ear and petechiae, and said he was 99% sure it was leukemia. He took some blood, hugged her, and called ahead to the ER, where she was diagnosed with high-risk B-cell ALL that night.

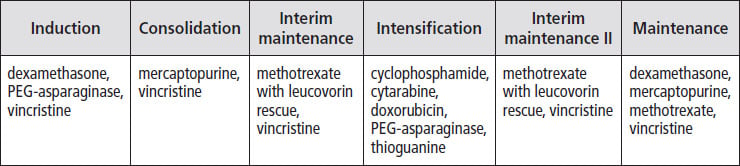

The table below shows the drugs most commonly used during each treatment phase for children with Down syndrome and B-cell ALL.

Protecting the heart. Because daunorubicin and doxorubicin can cause heart damage, some protocols include the drug dexrazoxane. This drug has been shown to protect the heart in some treatment protocols, and in some it has not been tested.

Asparaginase reactions. Some children have reactions to PEG-asparaginase, and in these cases, they are usually given a related medication called Erwinia L-asparaginase for the rest of treatment. Children who have severe reactions (e.g., grade 3 or 4 pancreatitis) usually do not receive any more of this drug.

CNS treatment. Intrathecal chemotherapy (injected into the spinal fluid during a spinal tap) is used for all children with Down syndrome and ALL. The chemotherapy drugs given to prevent spread of disease to the brain are:

- Cytarabine

- Methotrexate with leucovorin rescue

Cranial radiation. This is not used to treat children with B-cell ALL and Down syndrome.

My daughter was treated on the standard high-risk protocol for kids with Down syndrome. She was high risk because of her age. She was in the hospital for the first two weeks, then only occasionally for neutropenic fevers. They would culture her blood but nothing ever grew. She went through treatment without major toxicities or serious problems.

Table of Contents

All Guides- Introduction

- 1. Diagnosis

- 2. Overview of Childhood Leukemia

- 3. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

- 4. Acute Myeloid Leukemia

- 5. Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia

- 6. Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia

- 7. Telling Your Child and Others

- 8. Choosing a Treatment

- 9. Coping with Procedures

- 10. Forming a Partnership with the Medical Team

- 11. Hospitalization

- 12. Central Venous Catheters

- 13. Chemotherapy and Other Medications

- 14. Common Side Effects of Treatment

- 15. Radiation Therapy

- 16. Stem Cell Transplantation

- 17. Siblings

- 18. Family and Friends

- 19. Communication and Behavior

- 20. School

- 21. Sources of Support

- 22. Nutrition

- 23. Insurance, Record-keeping, and Financial Assistance

- 24. End of Treatment and Beyond

- 25. Relapse

- 26. Death and Bereavement

- Appendix A. Blood Tests and What They Mean

- Appendix B. Resource Organizations

- Appendix C. Books, Websites, and Support Groups