Childhood Brain and Spinal Cord Tumors

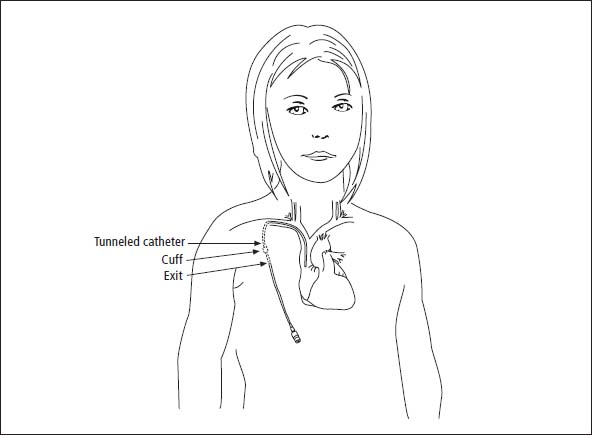

External catheter

The external catheter is a long, flexible tube with one end in the right atrium of the heart and the other end outside the skin of the chest. The tube tunnels under the skin of the chest, enters a large vein near the collarbone, and threads inside the vein to the heart (see Figure 9–1). Because chemotherapy drugs, transfusions, and IV fluids are put in the end of the tube hanging outside the body, the child feels no pain. Blood for complete blood counts (CBC) or chemistry tests can also be drawn from the end of the catheter. With daily care, the external catheter can be left in place for years.

The tube that channels the fluid is called a lumen. Some external catheters have double lumens in case two drugs need to be given at the same time. External catheters are usually put in under general anesthesia. Once the child is anesthetized, the surgeon makes two small incisions. One incision is near the collarbone over the spot where the catheter will enter the vein, the other is the area on the chest where the catheter exits the body. To prevent the catheter from slipping out, it is stitched to the skin where it comes out of the chest (see Figure 9–1). There is a plastic cuff around the catheter right above the exit site (under the skin) into which body tissue grows. This further anchors the catheter and helps prevent infection. After healing is complete, normal activities can resume.

Figure 9–1: External catheter

Daily care

The external catheter requires careful maintenance to prevent infection or the formation of blood or drug clots. It is necessary to frequently clean and bandage the site where the catheter exits the body (schedules range from daily to weekly). Procedures and schedules for daily cleaning and bandaging vary from one institution to another. Some pediatric oncology centers also place a small antibiotic-impregnated disk around the catheter at the exit site. The site should be checked daily for redness, swelling, or drainage.

To prevent clots, parents or older children are taught to flush the line with a medication called heparin that prevents blood from clotting. Each institution uses its own flushing schedule, and nurses at the hospital teach parents and children how to care for the catheter. Both parent and child should be given lots of time to practice with supervision and should not be discharged until they are comfortable with the entire procedure. At discharge, parents can arrange for home nursing visits to provide further help.

Risks

We were very grateful for Matthew’s Hickman® line. Like a lot of children, he was terribly afraid of needles. The maintenance that was necessary to keep his line working properly became second nature to me. After his diagnosis, and again after his relapse, he had a Hickman® implanted. In total, he had his external catheter for more than 4 years.

The major complications of using external catheter are infections—either in the blood or at the insertion site—and the formation of clots in the line or the vein where the catheter is placed. Rare complications include kinking of the catheter, the catheter moving out of place, or breakage of the external part of the catheter.

Infections

Even with the best care, infections are common in children with external lines. Children who have low blood counts for long periods of time are at risk for developing infections anyway, and each time the line is flushed or cleaned, there is a chance of contamination. Usually, it is a bacterium called staphylococcus epidermidis—which lives on the skin— that is the culprit, although a host of other organisms can cause infections in children receiving chemotherapy.

If your child develops a fever over 101° F (38.5° C), redness or swelling at the insertion site, or pain in the catheter area, you should suspect an infection. This is a life-threatening situation, so call the doctor immediately. To determine whether bacteria are present, blood will be drawn from the catheter to culture (i.e., grow in a laboratory for 24–48 hours). Treatment will start whenever an infection is suspected and will end if the culture comes back negative. If the culture is positive, treatment usually continues for 10–14 days. Some physicians require that the child be hospitalized for antibiotic treatment, while others allow the child to receive treatment at home. Treatment with antibiotics is usually effective. However, if the infection does not respond to treatment, the catheter will need to be removed.

When my daughter had a line infection, I wanted to use the antibiotic pump at home. It was hard, though. It took 2 hours per dose, three doses per day, for 14 days. I would get up at 5 a.m. to hook her up, so that she would sleep through the first dose. The second dose I would give while she watched a TV show in the early afternoon. Then I would hook her up at bedtime so she would sleep through it. I had to wait up to flush and disconnect, so I was very tired by the end of the 2 weeks.

Clots

We used the IV infusion ball when Joseph needed a 3-hour vancomycin infusion because he didn’t have to sit chained to a pump. The IV infusion ball is cool because if you have a sweatshirt with front pockets, you can make a tiny hole in the back of the sweatshirt to put the tubing through and stash the ball in the pocket so you can go about your business while your IV is infusing and no one has to know a thing! It’s handy for pain meds, too. He even used it at school, as long as I was there with him. An awesome invention—brilliantly simple. Here’s the website that describes it: www.iflo.com/prod_homepump.php.

Even with excellent daily care, some external catheters develop blockages or clots. If the catheter becomes blocked with a blood clot, it will be flushed with a drug to dissolve the clot, such as activase, urokinase, and streptokinase. These agents are given in the clinic or hospital, and the child usually needs to remain nearby for 1–2 hours. On rare occasions, the catheter becomes blocked by solidified medications, which can occur if two incompatible drugs are administered simultaneously. In those cases, a diluted hydrochloric acid solution may be used to dissolve the blockage.

Kinks

Two months before the end of Kristin’s treatment, her line plugged up. We tried several maneuvers at home unsuccessfully. We had to bring her in for the IV team to work on it. I think the bumpy ride to the hospital loosened it because at the hospital they were able to dislodge the clot just by flushing it with saline.

Rarely, a kink develops in the catheter due to a sharp angle where the catheter enters the neck vein. In such cases, the fluids may go in the catheter but it is hard to get blood out. Parents and nurses are often able to work around this problem by experimenting with different positions for the child when the blood is drawn. The nurse may ask your child to bear down as if having a bowel movement, take a deep breath, cough, stretch, or laugh.

Catheter breakage

My son is 16, and was diagnosed January 2001 with PNET. His Hickman® was giving the nurses problems, so they planned to do a dye study. They didn’t even have to inject the dye, the x-ray showed the line had come out and was clear across the opposite side of his chest and kinked! I don’t think it had been out long. But it was a little scary to think of that chemo maybe going everywhere. They did a procedure where they go in with a special catheter line and grab the IV and pull it back into place. It was still attached to the vein, so the chemo hadn’t been going amok. We are all so happy they got it fixed without surgery.

Breaks in the line do happen, but they are extremely rare. If a break or rupture of the line inside the body occurs when the line is not in use, only heparin will leak into surrounding tissues (not a major problem). If the break occurs when corrosive chemotherapy drugs are flowing through the catheter, they may leak and cause damage to surrounding tissue. The risk of an internal line leaking is far lower than the chance of leakage from an IV in a vein of the hand or arm.

The external portion of the catheter can also break. If this occurs, clamp the line between the point of breakage and the chest wall, cover the break in the line with a sterile gauze pad, and notify the doctor immediately. In most cases, the line can be repaired. Many institutions send a catheter repair kit home with parents.

Other factors to consider

I think it is important for parents to obtain clamps from the treating institution to carry with them. The preschool or school the child attends should also have one, in case something happens to the external line above the clamps that exist on the catheter. Younger children should wear a snug tank top that helps hold the catheter in place. Pinning it to the shirt is not the best solution for an active or younger child.

The proper care and maintenance of an external catheter requires motivation and organization. The site needs to be cleaned and dressed frequently, and heparin must be injected using sterile techniques. If your child’s skin is quite sensitive, or if she cries when tape or Band-Aids® are removed from her skin, the external line may not be the best choice because the dressing must be taped to the skin.

One of my most difficult times was learning to change the dressing for Ben’s catheter. I am totally freaked out by syringes, and anything like that, and here we were given a 10-minute demonstration in the hospital and an instruction book and that was it. I was petrified of doing something wrong to hurt my son. My husband tried, but he does not have very good balance, and he could not get the sterile gloves on without contaminating them. I went into panic mode the first week home from the hospital. I felt like the most inadequate mother in the whole world. Since neither of us could do what had to be done, my husband called a home health agency and they sent a nurse. Kathy was the most wonderful person on earth. She told me that even though she had been a nurse for 20 years, she didn’t think she could change the dressing on her own child, and she perfectly understood my fears. She had me watch her over and over again until I was comfortable enough to do it with her watching, and then finally on my own. She also talked to our insurance company numerous times to explain why she had to change the dressing instead of the family, and they ended up paying for her services! It was totally amazing. In addition, she helped my mental mood immensely, always telling me how good Ben was doing and sharing stories with me. I could tell her anything and she always understood. After I no longer needed her, she still stopped by about once a month to see how Ben was doing. She was my guardian angel.

The external line is a constant reminder of cancer treatment and can cause changes in body image. Both parent and child need to be comfortable with the idea of seeing and handling a tube that emerges from the chest. It is noticeable under lightweight clothing and bathing suits, but not under heavier clothing such as sweaters or coats. If a younger sibling might pull or yank on the catheter, the Hickman® or Broviac® might not be the appropriate choice.

On the other hand, the reason external lines are chosen so frequently is that there are no needles and no pain. This is a very important consideration for any children or teens who are scared of needles and/or pain. Some treatment protocols require double lumen access and the external catheter is the only option. For instance, children who need a stem cell transplant use double-lumen external venous catheters. But in most cases, families have a choice of which type of catheter to use.

Ben was diagnosed at age 5 with medulloblastoma, had a full resection, radiation to whole brain and spine, and one year of chemo. He had a double-lumen Broviac-Hickman®, a long tube with two ends that came out of his chest just above his right nipple. When not in use, it was curled and taped against his skin. I hated this thing. It made him Borg-like. I had to clean it every day for more than a year, and flush both ends of the tube. This hated thing, however, was what kept Ben from having to be stuck with needles several times a week. It was direct access to his blood supply, for tests, medication administration, and chemotherapy. One day Ben told me he had “made friends with his tubies.” They had names, “The red one was Ralph, and the white one was Henry.” He liked his tubies, he said, because they kept him from getting “ouchies.” I was speechless. His matter-of-fact example showed me that the sooner I made friends with Ralph and Henry, the better off I’d be.

Children with external catheters have restrictions about contact sports, swimming, use of hot tubs, and sometimes bathing and showering, although care protocols vary by institution.

Table of Contents

All Guides- Introduction

- 1. Diagnosis

- 2. The Brain and Spinal Cord

- 3. Types of Tumors

- 4. Telling Your Child and Others

- 5. Choosing a Treatment

- 6. Coping with Procedures

- 7. Forming a Partnership with the Treatment Team

- 8. Hospitalization

- 9. Venous Catheters

- 10. Surgery

- 11. Chemotherapy

- 12. Common Side Effects of Chemotherapy

- 13. Radiation Therapy

- 14. Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation

- 15. Siblings

- 16. Family and Friends

- 17. Communication and Behavior

- 18. School

- 19. Sources of Support

- 20. Nutrition

- 21. Medical and Financial Record-keeping

- 22. End of Treatment and Beyond

- 23. Recurrence

- 24. Death and Bereavement

- 25. Looking Forward

- Appendix A. Blood Tests and What They Mean

- Appendix C. Books and Websites