The brain, cushioned by watery fluid on all sides, resides inside the skull. It resembles a fleshy, shelled walnut in shape. Like a walnut, it has two distinct but connected halves. These are called the left and right cerebral hemispheres. Although the hemispheres appear to be mirror images of each other, the similar-looking parts of each do different things.

Like a walnut’s exterior, the brain’s surface folds in and out. These wrinkles increase the surface area of the brain. Its surface is divided by especially deep grooves, called fissures or sulci. The brain contains major nerves—such as the optic nerves, which connect it to the eyes. There are also nerves that control movement of arms and legs, the ability to maintain a heart rate, and level of awareness. Blood vessels carry oxygen and nutrients to all parts of the brain and spinal cord, and channels called aqueducts allow the watery fluid (called cerebrospinal fluid [CSF]) to move throughout the brain and spinal cord (central nervous system or CNS).

The brain has several protective coverings that prevent injury. The bones of the skull and the spine provide the outermost protection. Inside the skull are three thin membranes called the meninges, which surround the brain and spinal cord. The outer meninge is called the dura mater, the inner meninge is the pia mater, and the middle meninge, which carries the blood vessels, is called the arachnoid (see Figure 2–1). The brain and spinal cord are also protected by the CSF that flows between the layers of meninges.

Figure 2–1: The meninges

Cerebrum

The largest region in the brain is the cerebrum (also called the supratentorial region). It is made up of two cerebral hemispheres (left and right). The two hemispheres are separated by a large groove, called the cerebral fissure. Deep within the cerebral fissure is a bundle of nerve fibers called the corpus callosum, which transmits information between the two sides of the cerebrum.

The cerebrum interprets sensory input from all parts of the body and also controls body movements. It is the part of the brain responsible for thinking, reasoning, learning, controlling movement, and processing emotions and memories.

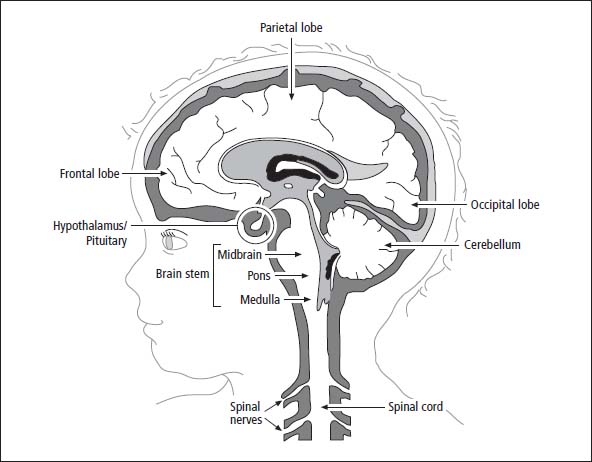

The cerebrum is divided into four areas (called lobes) on each side of the brain: the frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes. The corpus callosum connects the two parts of each lobe on both sides of the brain. Structures on one side of the brain control the opposite side of the body. For example, any movement of the arms and legs on the right side of the body is controlled by the left cerebral hemisphere.

Your child’s doctors will attempt to determine which side of your child’s brain is dominant. Dominance is important for tumors that are near the hearing or speech and language processing areas. It may be difficult for the surgeon to remove all of the tumor on a dominant side in these areas without damaging speech or hearing. Pre-operative testing (functional MRI scans) and intraoperative monitoring (mapping) are vital when dealing with tumors in the dominant hemisphere. These tools, discussed in Chapter 6, Coping with Procedures, and Chapter 10, Surgery, allow the surgeon to remove as much tumor as possible while preserving function. The parts of the cerebrum are shown in Figure 2–2.

Frontal lobes

The frontal lobes, located directly behind your forehead, are your brain’s main planning and personality centers. They process and store information that helps you think ahead, use strategy, and respond to events based on past experiences and other knowledge. A small part of the frontal lobe is involved in articulating speech. Another small strip of the frontal lobe helps control movement. Malfunctions in the frontal lobe may lead to poor planning, impulsiveness, and certain types of speech problems. Symptoms are more pronounced if the tumor crosses the corpus callosum and affects both frontal lobes. Symptoms of frontal lobe tumors include:

- Seizures

- Changes in ability to concentrate

- Poor school performance

- Changes in social behavior and personality

Figure 2–2: Basic brain anatomy

Toward the back section of the frontal lobe is the motor cortex, the part of the brain that controls movement of the head and body parts on the opposite side of the body. Because the location of motor nerves varies a little in each person, mapping of the motor cortex using a functional MRI, and using this information while monitoring during surgery, helps surgeons know the exact location of these nerves so as not to injure them during tumor removal. For more information, see the “MRI” section of Chapter 6, Coping with Procedures, and the “Intraoperative monitoring” section of Chapter 10, Surgery.

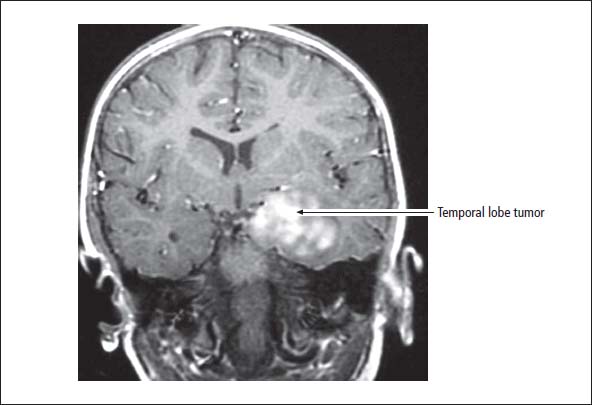

Temporal lobes

The temporal lobes are located at the sides of the brain. Hearing, memory, and speech and language processing are managed by the temporal lobes. They are the places where information taken in from the various senses is integrated, permitting complex thoughts, movements, and sensations to be formulated and acted upon. Within the temporal lobes is the amygdala, which controls social behavior, aggression, and excitement. The hippo-campus, located in the temporal lobes, is involved in storing memories of recent events. Depth perception and sense of time are also controlled by the temporal lobes.

Tumors in the temporal lobes can cause seizures and changes in behavior. When a tumor grows in the temporal lobes, the brain has a hard time filtering out extra information, and sensory information and memories may start to blend together in unfamiliar ways. Sounds may be perceived as having colors, for example, or your child may have an unsettling feeling of déjà vu.

Our son is now 6 years old, and he’s had his brain tumor since he was a baby, so he’s lived with it for quite a while. He has partial complex seizures that cycle from one a week to two or three times a day for a couple days a week. This has been going on regardless of what medication we’ve used, so far.

They start with a blank stare, then he says, “Um, um” or “Mom, Dad” a few times, or sometimes, if it’s at night, he may be more disoriented and cry out. Then he flushes pink, sometimes he smacks his lips or picks at his clothes with his fingers. At one point, you can tell he can’t hear or even see, but then he becomes more aware, and he’ll take a breath when we ask. Then he usually spits up and wants to nap.

And the medications can cause their own side effects, like dull affect, behavior changes, and light sensitivity. Our neurologist’s office had a poster up about an epilepsy support group in the area, so I’ve been going to those.

Figure 2–3: MRI showing temporal lobe tumor

Parietal lobes

Directly behind the frontal lobes and above the temporal lobes are the parietal lobes. In some people, the motor cortex, which controls arm and leg movement, extends into the parietal lobes. The parietal lobes process all sorts of sensory information coming in from the body, including data about temperature, pain, and taste. The parietal lobes also control language and the ability to do arithmetic. When the parietal lobes are not functioning properly, sensory information is not processed correctly, and your child may have a hard time making sense of her environment.

The rear of each parietal lobe, next to the temporal lobe, has an area important in processing the auditory and visual information needed for language. When children have tumors in these lobes, they do not understand what is being said when someone speaks to them.

Abnormal movements or weakness in the arms and legs, memory problems, language problems, and seizures are associated with tumors in the parietal lobes. During a seizure affecting these areas, strange physical sensations may be felt, such as a crushing pressure or a tingling feeling in part of the body.

Occipital lobes

Megan was 20 months old when we found out that she had an anaplastic ependymoma occupying the entire left occipital-parietal region of her brain (about half the size of her little head). For 6 to 8 weeks, she had sporadic vomiting and crabbiness in the morning. By the time we’d arrive at the doctor’s office, she would be fine. Then she developed a right-sided tremor that was so strong it shook her whole body when she tried to use her right arm. The pediatrician ordered an MRI and found the brain tumor.

The occipital lobes serve as the visual centers of the brain. They are responsible for making sense of the information that comes to the brain from the eyes through the optic nerves. The left occipital lobe deals with input from the right eye, and the right lobe deals with input from the left eye. Tumors in the occipital lobes are associated with visual field cut (loss of central or peripheral vision) on one side or the other.

Posterior fossa

The posterior fossa (also called the infratentorium) is located at the very back of the brain, on top of the spinal cord. It includes the cerebellum, the brainstem, and the fourth ventricle (see the “Ventricular system” section and Figure 2–6 later in the chapter).

Figure 2–4: Side view of the brain

Sixty percent of all childhood brain tumors originate in the posterior fossa. Symptoms of tumors in this area of the brain include:

- Signs of increased intracranial pressure (headache, vomiting, unsteady gait, double vision, sleepiness, or lethargy)

- Weakness of cranial nerves (visual or hearing problems, weakness or drooping on one side of the face, eye movement problems, difficulty swallowing, difficulty breathing)

- Unsteady gait (ataxia)

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is about one-eighth the size of the cerebrum. Tumors growing in the cerebellum can cause coordination and balance problems. The child may have an uneven walking pattern or may continually fall to one side. Difficulty judging distances or reaching for and grabbing an object are symptoms of a tumor in this area.

Brainstem

Red-headed, 2-year-old Matthew had vomiting almost every day. After 3 months of running back and forth to the doctor, the babysitter and I noticed some “tipsy walking,” as we called Matt’s ever-so-subtle dizziness. A call to the doctor with this report led us to the office of a neurologist. A neurological exam and a little observation found us with an order to have an MRI to rule out a brainstem tumor. The neurologist was sure the diagnosis was going to be benign vertigo of infancy, something usually outgrown by the age of 3. Whew, 1 more year of the vomiting and we’d be done. Wrong again. The neurologist told us our son had a brain tumor (medulloblastoma, on the floor of the fourth ventricle), that it was malignant, and he would need surgery as soon as possible. His tumor was located in the cerebellum, at the base of the brainstem, right where the circuits for all vital functions are connected.

The brainstem is the relay center for transmitting messages between the brain and other parts of the body. All sensory information from the body goes through the brainstem on its way to the rest of the brain, and all motor messages from the brain to the rest of the body travel through the brainstem. The three parts of the brainstem are:

- Midbrain, which processes vision and hearing and coordinates sleep and wake cycles

- Pons, which controls eye and facial movements and links the cerebellum to the cerebrum

- Medulla, which controls breathing, swallowing, heart rate, and blood pressure

The 12 cranial nerves originate in the brainstem, primarily in the pons and medulla. They control eye and facial movements, vision, taste, hearing, swallowing, and movement of the neck and shoulders.

Symptoms of tumors in the brainstem include:

- Abnormal eye movements or a droopy eyelid

- Drooping of the face or facial asymmetry

- Difficulty swallowing or breathing

- An uneven walking pattern

- Weakness on one or both sides of the body, often seen first in an arm and/or a leg

Diencephalon

Ayla’s eyes were “off” from each other. Her right eye would look at you and the left eye would go off. Our pediatrician thought it could be cross-eye, and suggested waiting it out, but in another week, her eye was completely turned in and you couldn’t even see the pupil. The eye doctor we saw said there was no reason that he could see for her eyes to cross, so we went to a neurologist, who did a neurological exam, and said Ayla showed no neuro problems. But, he ordered a scan just in case, not expecting to find anything. He thought it could possibly be a virus. The scan found a 5x5 cm tumor in the posterior fossa, cerebellopontine angle, fourth ventricle, and arising from the brainstem.

Near the center of the brain is the diencephalon, which is made up of several tiny but extraordinarily important structures: the thalamus, the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the pineal gland.

All sensory information passes through the thalamus before being sent to the forebrain for more advanced interpretation—except for information gathered via the sense of smell, which takes a different route. The hypothalamus is small, but it has a big role in managing everything from hunger to digestion to muscle contractions. It has direct control over the pituitary gland, which produces hormones and similar chemicals. The pineal gland helps to govern the body’s sense of time and rhythm, including regulation of the reproductive cycle.

Tumors that grow in the diencephalon cause:

- Disruption of hormone production

- Abnormal growth (usually delayed growth)

- Excessive thirst and frequent urination

- Drowsiness or changes in level of consciousness

- Difficulty with vision

- Memory problems

- Weakness of one or both sides of the body

Optic nerves

Florence has recovered from a germinoma, a malignant tumor of the pituitary gland. She was ill from ages 11 to 15, and the diagnosis took 2 years. This tumor seems to be very rare. Prior to diagnosis, there was a long period of weight loss, incessant thirst, and teachers and doctors who kept saying this was all psychological. Florence would get up in the morning, go to the kitchen, and start the awful drinking, glass after glass. One time I really lost it. I shouted at her, “Why are you doing this? Do you know what you are doing? You are going to make yourself very ill. Do you know what manipulative behavior is?” I shouted and shouted; she didn’t argue or cry. She just stood there and smiled at me sadly. She said, “I just can’t help it.” I thought, “That is it. This is a real illness.” By then she was thin and she hadn’t grown for months.

A young doctor gave her an injection of vasopressin. The effect was miraculous; she ran along the corridor, skipped up and down, she felt marvelous. The young doctor came back, very excited. He said, “We have a very good result.” I stared at him. He said, “Well, perhaps a bad result from your point of view. Florence has diabetes insipidus. This is a permanent condition, the hormone which governs her kidneys is not being produced, and she has been drinking to stop herself from dying of dehydration.” After more searching, I finally found a consultant, and when he heard the symptoms, he said he knew what the cause could be. It was a germinoma—a rare tumor whose symptoms often begin with diabetes insipidus.

The optic nerves carry information from the eyes to the occipital lobes. The nerve from the right eye goes to the left occipital lobe, and the nerve from the left eye goes to the right occipital lobe. These two nerves cross at a place called the optic chiasm, near the hypothalamus. Tumors that affect the optic nerves cause changes in visual acuity (the ability to see) or visual fields (peripheral vision).

After they discovered the optic tract tumor on the MRI, they sent us to vision specialists at the eye clinic. There Jamie saw an ophthalmologist who checked for optic nerve swelling, an orthoptist who checked acuity, and a visual function specialist, who found a complete loss of left-sided peripheral vision. The field cut is especially noticeable when he’s in new environments, and he bumps into things on the left, although mostly he remembers to make the extra effort to turn his head to check out things on that side.

Table of Contents

All Guides- Introduction

- 1. Diagnosis

- 2. The Brain and Spinal Cord

- 3. Types of Tumors

- 4. Telling Your Child and Others

- 5. Choosing a Treatment

- 6. Coping with Procedures

- 7. Forming a Partnership with the Treatment Team

- 8. Hospitalization

- 9. Venous Catheters

- 10. Surgery

- 11. Chemotherapy

- 12. Common Side Effects of Chemotherapy

- 13. Radiation Therapy

- 14. Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation

- 15. Siblings

- 16. Family and Friends

- 17. Communication and Behavior

- 18. School

- 19. Sources of Support

- 20. Nutrition

- 21. Medical and Financial Record-keeping

- 22. End of Treatment and Beyond

- 23. Recurrence

- 24. Death and Bereavement

- 25. Looking Forward

- Appendix A. Blood Tests and What They Mean

- Appendix C. Books and Websites