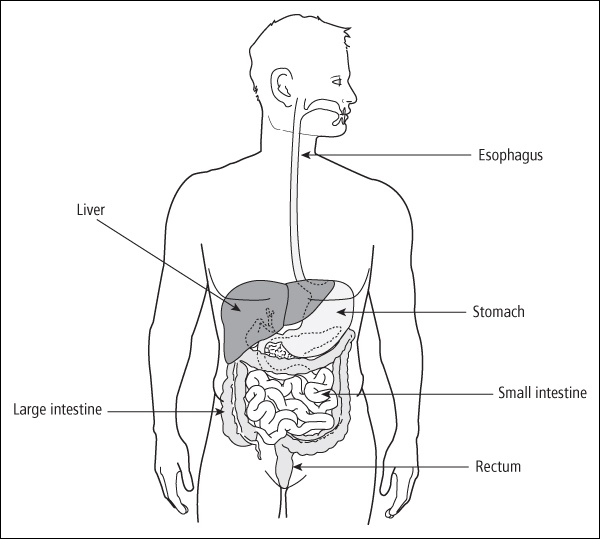

The liver is the body’s largest internal organ and one of the most complex. This wedge-shaped organ is located beneath the rib cage in the upper-right part of the abdomen.

The liver performs thousands of functions that are essential to life. It converts food into energy, removes toxins (e.g., alcohol and drugs) from the body, keeps blood clotting normally, and manufactures proteins. It regulates the supply of essential minerals and vitamins and also produces bile, a fluid needed for proper digestion. In addition, the liver helps filter many chemical substances and waste products from the blood.

Figure 15-1 shows the location of the liver, stomach, and intestines.

Organ damage

Inflammation of the liver is called hepatitis from the Latin word for liver, hepar , and the Greek word itis , meaning inflammation. There are many possible causes of liver inflammation in childhood cancer survivors, including infection by viruses and damage from radiation and/or chemotherapy drugs. However, inflammation of the liver is relatively rare in survivors, especially in those treated in the last decade.

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is an infection caused by the hepatitis A virus, which is usually spread by contamination of food by human waste. Approximately 150,000 cases are diagnosed in the United States each year. It is most common in international travelers, sexually active homosexual men, intravenous drug users, and daycare workers. Most healthy people who get hepatitis A have no long-term consequences from the infection. There is an effective vaccine that prevents hepatitis A infections. This type of hepatitis is not a late effect of childhood cancer.

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is an inflammation of the liver caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV). Approximately 1 million Americans have chronic hepatitis B infections, including survivors who received blood transfusions prior to 1972 (blood products were not screened for this virus before 1972). There is now an effective vaccine that prevents hepatitis B infections. The blood supply for transfusions is now well screened, and healthcare workers are routinely vaccinated.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is an inflammation of the liver caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV). HCV was spread by blood transfusions that were received prior to effective testing of blood products, and is currently spread by sharing needles for illicit intravenous drug use, and, less commonly, through sexual intercourse. Approximately 3.2 million people in the United States are infected with the HCV, making it the most common chronic blood-borne infection in the United States. There is no vaccine for HCV.

Before July 1992, there were no available laboratory tests to identify blood carrying HCV, and some children and teens with cancer received infected blood. Because more effective tests for the virus have been used by blood banks since July 1992, the current risk of getting HCV from a single blood transfusion is very small—only 1 per 2 million units transfused.

If you are infected with HCV, there are five possible outcomes:

-

Your body’s immune system may eliminate the virus and you will have no further problems (this happens in 15 to 25 percent of persons infected). 1

-

You may have a lifelong infection, but your liver will sustain no damage.

-

You may develop liver inflammation, with or without symptoms.

-

You may develop progressive inflammation and scarring of the liver. When this scarring (fibrosis) is spread throughout the liver and causes lumps, it is called cirrhosis. This process occurs over many years and usually results in symptoms. It can eventually lead to liver failure.

-

In rare cases, liver cancer develops, but only after years of inflammation from chronic hepatitis C and cirrhosis.

Liver Fibrosis

Liver fibrosis (excessive formation of scar tissue) develops from liver inflammation, which has a variety of causes. Risks for development of liver fibrosis due to radiation are as follows:

-

The amount of the liver that was irradiated

-

The radiation dose

-

Younger age at treatment

-

Certain chemotherapy drugs (i.e., dactinomycin and doxorubicin) given in addition to radiation 2

Survivors at highest risk are those who had 2,000 cGy or more to the entire liver. 3

Chemotherapy can also cause liver fibrosis. Early protocols for acute lymphoblastic leukemia that gave daily oral methotrexate for 2 to 5 years caused liver fibrosis in up to 80 percent of children. 4 Very few children who received lower doses of methotrexate develop fibrosis. However, survivors of leukemia who have HCV and were treated with methotrexate are at increased risk for liver fibrosis. 5 Much less frequently, mercaptopurine (6-MP), thioguanine (6-TG), and dactinomycin can affect the function of the liver.

Survivors of stem cell transplantation (e.g., bone marrow, peripheral stem cell, or cord blood transplants) may have several risk factors for chronic liver disease, including HCV infection, iron overload, and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). One large study of more than 3,000 patients from the Fred Hutchinson Research Center estimated that 20 years after transplant, 3.8 percent of survivors had developed chronic liver disease. 6 Liver damage can develop rapidly in transplant survivors.

The risks for liver fibrosis are:

-

Liver toxicity during treatment (high results on liver function tests many different times).

-

Chronic viral hepatitis.

-

Liver irradiation (abdominal radiation on the right side).

-

High doses of drugs that can cause liver toxicity (e.g., methotrexate, 6-MP, 6-TG, dactinomycin).

-

Stem cell transplantation.

Signs and symptoms

Because HCV can silently damage the liver, you may not be aware of the infection until the late complications of liver disease cause symptoms many years later. Though most people with HCV have no symptoms at the onset of the infection, some may experience the following:

-

Jaundice (yellowish eyes and skin)

-

Fatigue

-

Loss of appetite

-

Fever

-

Nausea and vomiting

-

Pale or clay-colored stools

-

Dark urine

-

Generalized itching

-

Diarrhea

Signs and symptoms of liver fibrosis are as follows:

-

Nausea and vomiting

-

Fluid buildup in the abdomen

-

Enlarged liver or spleen

Screening and detection

Your regular yearly examination should include a discussion about your liver and history of blood transfusions. You should get your blood tested for HCV if any of the following apply to you:

-

You have been notified that you received blood from a donor who later tested positive for HCV.

-

You received any blood products before 1993.

-

You had a solid organ transplant before 1993.

-

You have a history of illicit intravenous drug use.

-

You have signs or symptoms of liver disease (for example, abnormal liver enzyme tests or an enlarged liver).

I had multiple blood transfusions in 1974, 1980, 1981, 1982, and 1984. In January 1998, I was at my internist’s office getting blood work done. I told the doctor that my husband and I were going on our vacation to Cancun, Mexico, in the summer. He suggested I get a hepatitis test to see if I needed to get a hepatitis vaccination.

Lo and behold, the blood work came back positive for hepatitis C, antibodies for hepatitis B, but negative for hepatitis A. He then ran another blood test to determine the viral load (how much of the hepatitis C was in my system).

After that I was referred to a hepatologist at Baylor-Dallas. He did a liver biopsy in April 1998 to determine how much damage had been done to my liver and ran blood work to determine what genotype (or subtype) of hepatitis C I had. I had the genotype 2B, which is one of the easier ones to treat. This type often goes into remission with treatment.

In February 1999, I started on the combo treatment called Rebetron ® , which is made up of interferon injections and capsules called ribavirin. The FDA had just approved it. So from February to August I endured these treatments, and the disease is now in remission. The viral load for hepatitis C is now undetectable.

Most institutions recommend three blood tests (ALT, AST, and bilirubin) on entry to a long-term follow up program. Stem cell transplant survivors should also have a serum ferritin test. All survivors treated prior to 1972 should be tested for hepatitis B and survivors treated before 1993 should be tested for hepatitis C. 7 During your annual physical examination, your healthcare provider should palpate (feel) your abdomen to check for an enlarged liver. Any abnormal findings should result in a referral to a gastroenterologist for further evaluation and treatment.

A small number of survivors who have had chronic HCV and develop cirrhosis may develop a type of liver cancer called hepatocellular carcinoma. The chance of developing this cancer is greatly increased in those who drink alcohol. To screen for this type of cancer, survivors with cirrhosis periodically need a blood test (called alpha-fetoprotein) done.

Medical management

There is no specific treatment for acute HCV. Rest may be recommended during the acute phase if symptoms are severe. The acute infection usually disappears 3 to 4 months after symptoms begin.

Chronic HCV can be treated with a number of medications. Interferon alpha, which stimulates the immune system to fight the infection, and ribavirin, an antiviral antibiotic, are usually given together. This combination treatment is effective in up to half of patients. Treatments for HCV are evolving and improving, so keep in touch with a specialist if you have HCV to learn of the newest options.

Some people who have had HCV infections for many years need a liver transplant, because the liver becomes so damaged that it can no longer perform its crucial functions.

If you have HCV or chronic liver fibrosis, you can do the following to protect your liver:

-

Don’t drink alcohol—it greatly increases damage to the liver. This includes even occasional beer or wine.

-

Don’t take over-the-counter medications, such as Tylenol ® (acetaminophen) or Advil ® (ibuprofen), herbal or dietary aids, or prescription medications, without first discussing them with your healthcare provider. Many of these can cause more damage to the liver. Read labels of other over-the-counter drugs to make sure they don’t contain acetaminophen or ibuprofen.

-

Get vaccinated against hepatitis A and B.

-

See your healthcare provider regularly.

HCV can be spread to a partner by sexual intercourse, so it is important to use barrier protection, such as condoms. Because there is no vaccine against HCV, a spouse (or sexual partner) of a survivor with HCV can also get the infection. Therefore, your spouse (or sexual partner) should be periodically screened for HCV. Rarely, HCV can be transmitted to an infant during pregnancy. It is important that female survivors with HCV tell their obstetrician and family physician about the infection.

Counseling should be provided if you test positive for HBV or HCV to help you learn about and cope with these chronic diseases. Many people with HCV infections find comfort participating in support groups, which are available in many communities because HCV is so widespread.

For more information about HCV, read the frequently asked questions on the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention hepatitis C website at www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/index.htm or call (800) CDC-INFO (800-232-4636). The American Liver Foundation has an informative website at www.liverfoundation.org . Other helpful organizations are listed in Appendix B .

Table of Contents

All Guides- 1. Survivorship

- 2. Emotions

- 3. Relationships

- 4. Navigating the System

- 5. Staying Healthy

- 6. Diseases

- 7. Fatigue

- 8. Brain and Nerves

- 9. Hormone-Producing Glands

- 10. Eyes and Ears

- 11. Head and Neck

- 12. Heart and Blood Vessels

- 13. Lungs

- 14. Kidneys, Bladder, and Genitals

- 15. Liver, Stomach, and Intestines

- 16. Immune System

- 17. Muscles and Bones

- 18. Skin, Breasts, and Hair

- 19. Second Cancers

- 20. Homage

- Appendix A. Survivor Sketches

- Appendix B. Resources

- Appendix C. References

- Appendix D. About the Authors

- Appendix E. Childhood Cancer Guides (TM)