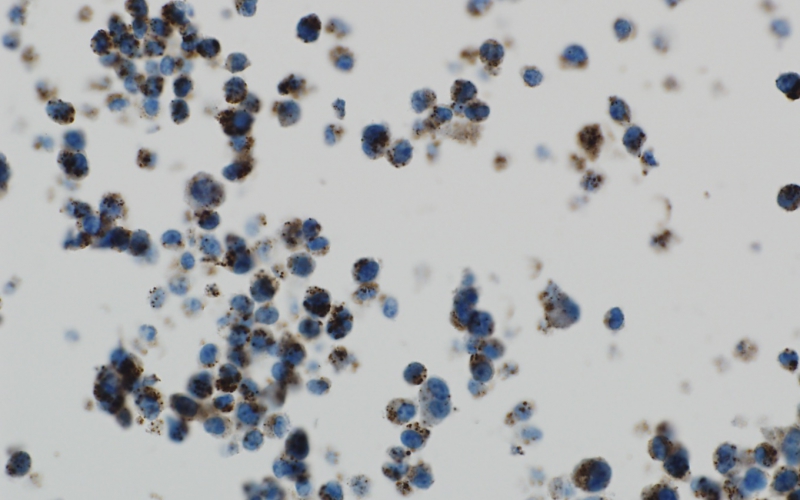

An ALSF-funded researcher is working to combat the process of autophagy and destroy brain tumor cells. Above, brain tumor cells under stress show a high level of autophagy, as exhibited by the brown spots.

by Trish Adkins

In order to survive, the cells of the body are constantly recycling within themselves, taking proteins inside the cell, scooping them up, breaking the proteins down and releasing the energy back into the cell as new building blocks. Every cell in the body performs this process, called autophagy. The word literally means “self-eating,” and in addition to giving cells an internal source of energy, autophagy also helps cells remain healthy by keeping invaders like bacteria, viruses or chemotherapy out. Cells that live in harsh environments—environments like the brain where cells have limited blood supply—are skilled at using autophagy to survive.

Brain tumor cells are experts at autophagy and use the process to survive chemotherapy, becoming resistant to treatment, leaving doctors without effective tools to stop cell growth and leaving children and their families without hope for a cure.

Until now.

Jean Mulcahy Levy, MD, an ALSF Young Investigator grant recipient, is studying how stopping autophagy can be an effective treatment for some types of brain tumors.

Autophagy: Key to Cell Survival

Dr. Levy's research on autophagy is based on the discovery of the 2016 Nobel Prize winning scientist Yoshinori Ohsumi. Ohsumi first detected the process of autophagy in yeast. The process helps explain how human beings can survive in extreme situations, like starvation, and also how cancer cells can survive treatments that should work, but simply do not.

Anytime cells become stressed out—whether by treatment or cell environment—they ramp up their recycling process to survive.

Autophagy and the BRAF Mutation

Dr. Levy’s research discovered that brain tumors with a BRAF mutation inhibiting autophagy can stop the tumors from becoming treatment resistant, allowing chemotherapy to work and eliminate disease.

The BRAF mutation is the most common genetic mutation found in human cancers and is found across a variety of low grade and some of the harder to treat high-grade brain tumors, such as high-grade glioblastoma.

Dr. Levy used chloroquine, a medicine originally created to treat malaria in the 1950s, to inhibit autophagy. Since it is already approved for patient use, the drug is safe and readily available. In the treatment of malaria, chloroquine stopped the malaria parasite from living in the blood cells. In the treatment of brain cancer, Dr. Levy’s hope was that chloroquine would stop autophagy and overcome the resistance to chemotherapy, killing the brain cancer cells and bringing children closer to a cure.

And it worked.

In Dr. Levy’s lab tests and with three patients battling relapsed brain tumors with the BRAF mutation, chloroquine used in conjunction with chemotherapy and radiation resulted in positive clinical outcomes. The brain tumor cells became susceptible to chemotherapy protocols.

The next step for Dr. Levy’s research is a clinical trial, which will expand the number of patients treated and continue to prove the safety and efficacy of chloroquine for autophagy inhibition in patients with the BRAF mutation.

“Identifying new treatment options like autophagy inhibition, allows us to treat patients who have exhausted treatment options,” says Dr. Levy. “It also provides another option for patients for whom newer immunotherapies have failed.”

Dr. Levy’s work, “Autophagy inhibition overcomes multiple mechanisms of resistance to BRAF inhibition in brain tumors,” was published in the January 17, 2017 issue of eLife.

Read more about Dr. Levy’s work here.