The Childhood Cancer Blog

The Childhood Cancer Blog

Children with certain types of hard-to-treat childhood cancers just got another huge dose of hope. Last week, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted accelerated approval to a drug called Vitrakvi (also known as larotrectinib), making the treatment available to children with cancers that are NTRK fusion-positive.

... Read More

Hailing from all over the world, the 90 researchers were invited to the first-ever ALSF Crazy 8 meeting in Philadelphia in September 2018.

The most common type of extra-cranial childhood cancer in children, neuroblastoma has seen an increase in long-term survival rates over the past 10 years (from 30% to 50-60%, depending on stage of disease and age at diagnosis). However, the hardest, high-risk neuroblastoma continues to be tricky to cure, requiring years and years of harsh treatments that leave children with long-term side effects.

Making up the largest group of brain tumors, embryonal brain cancers include medulloblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma and other subtypes. The standard of care for embryonal brain tumors is surgery, radiation and intensive chemotherapy. Each of these treatments comes with the potential for severe side effects.

High grade gliomas, which include DIPG and ependymoma, are notoriously hard to treat because of their location in the brain and their fast growing nature. Presently, DIPG has a zero-percent long-term survival rate.

While some types of leukemia, like acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), have long-term remission rates of around 90-percent; relapsed and refractory ALL and other less-common leukemias, like acute myeloid leukemia (AML), are harder to treat and present significantly lower remission rates.

Fusion positive sarcomas form as the result of a genetic chromosomal transcription that creates a new malignant cell. Ewing sarcoma is the most prominent example, but other cancer types like alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma can also be fusion positive.

Fusion negative sarcomas are sarcoma-type cancers that do not have abnormalities that follow a specific genetic pattern, like fusion positive sarcomas.

Researchers have long struggled with the accessibility and availability of pediatric oncology data. The first challenge is the general lack of genetic models because of the rarity of some types of childhood cancer. The second challenge is the reverse—there are millions of data sets, all written in different formats and therefore hard to access and utilize.

Clinical trials are one of the critical ways that researchers can test and discover treatments that work in children. Trials are also the key step on the way to setting new standards of care. Crazy 8 researchers know that trials can be done more efficiently and remove roadblocks, such as funding for research, to accelerate cures.

by Trish Adkins

In September, Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation (ALSF) called over 90 top scientists, pediatric oncologists and researchers from around the world to gather in Philadelphia to discuss the big question:

How can we cross the finish line and find cures for all children fighting cancer?

The meeting kicked off the Crazy 8 Initiative—ALSF’s commitment to identifying obstacles, knocking down roadblocks and developing a comprehensive, achievable plan to foster research, collaborate and accelerate cures... Read More

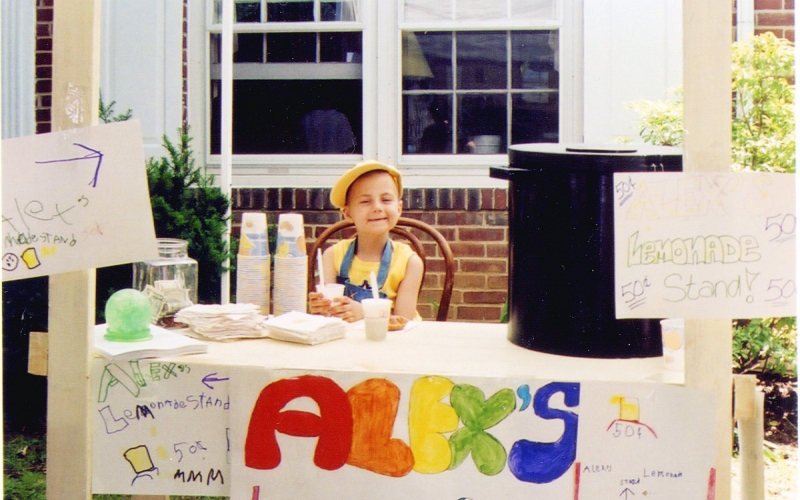

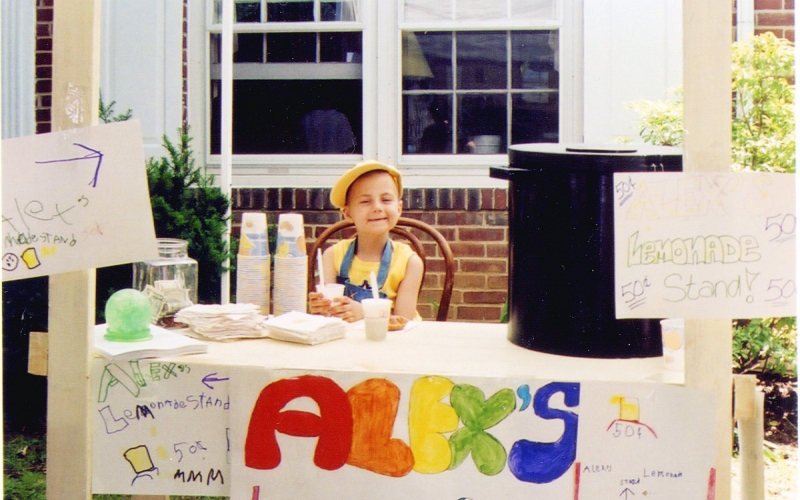

Alexandra “Alex” Scott said it best: “I think if we all work together, we can do it.”

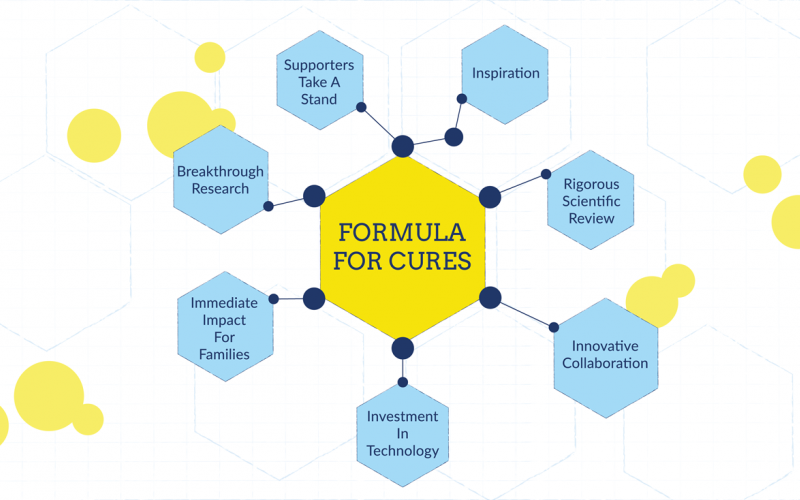

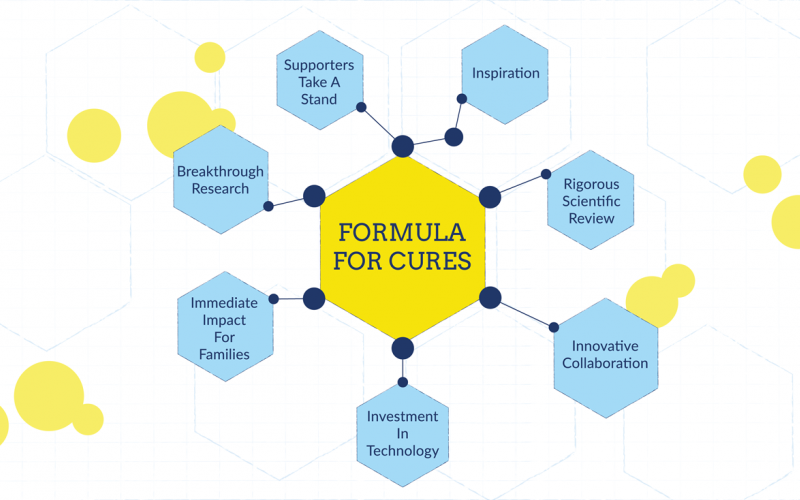

This is ALSF’s Formula for Cures. It starts and ends with the inspiration of supporters, heroes and researchers.

Alex Scott inspired supporters everywhere to make a difference—from stand hosts to corporate partners to children to adults to researchers—each of us has a contribution to make towards cures.

To maintain our dedication to rigorous scientific review, the Crazy 8 Initiative will create a roadmap to tackle the most pressing problems facing researchers.

Each year, ALSF-funded Young Investigators gather to share their research, network and collaborate on ways to innovate their research.

Accelerating breakthrough research for hard to treat cancers like DIPG is critical. ALSF-funded researcher, Dr. Michelle Monje, recently discovered that a type of immunotherapy shows promise in the treatment of this deadly brain tumor.

Willow’s family needed to make a 1,000 mile road trip every three months for her treatment for a rare brain tumor. The ALSF Travel for Care program was able to provide her with immediate financial support to receive her treatment at a facility far from home.

There is enough publicly available disease data at the National Institute of Health to fill up several hundred Libraries of Congress and through ALSF’s investment in technology, the Childhood Cancer Data Lab is translating that data into one consistent format for researchers to access and use.

Supporters, like the Lemonettes, take a stand every day for cures. The sister duo has raised more than $15,000 since 2012.

The inspiration for all the work we do begins and ends with our supporters. Dr. Glen Samuels and his patient, Malina, worked together to identify a biomarker for Ewing sarcoma. Dr. Samuels used Malina’s donated blood sample in the lab to study what happens in the blood when a child has Ewing sarcoma.

by Trish Adkins

Starting with her very first lemonade stand, Alexandra “Alex” Scott, Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation (ALSF) founder, sparked a movement—a movement not only to help sick kids get better and find cures for childhood cancer; but one that would inspire and call on each one of us to work together.

Over the last 13 years, childhood cancer heroes and their families, donors, volunteers, and of course, researchers have come together for one goal: cures for childhood cancer.

At ALSF, we have learned that curing childhood cancer is not just a product of... Read More

Pages