by Trish Adkins

When a child receives the diagnosis of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), the diagnosis comes with an end date.

Thus far, DIPG is always lethal.

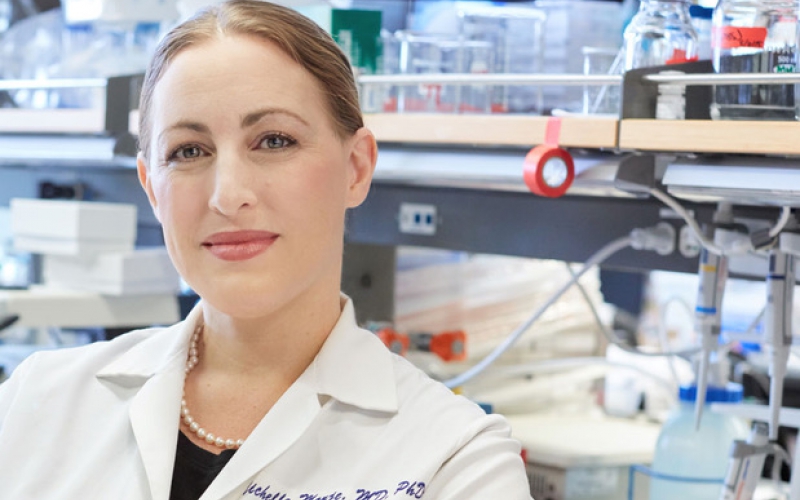

But, ALSF-funded grantee Dr. Michelle Monje of Stanford University, does not believe it has to be. Dr. Monje, who specializes in studying high-grade gliomas, is close to a powerful breakthrough that could change the prognosis for children with DIPG.

“The amount of progress that has been made in the study of childhood gliomas in the past five years is more than has been made in the last 50 [years]. It is a really exciting moment of progress and hope,” said Dr. Monje.

Dr. Monje recently demonstrated that a certain type of CAR T Cell immunotherapy killed DIPG cells in murine models. CAR T Cell immunotherapy has been approved to treat certain types of pediatric leukemia and has proven effective in clinical trials for other types of the childhood cancer. In Dr. Monje’s lab, these engineered immune cells were given intravenously and then went directly to work clearing the tumor cells in the brain. The result: instead of seeing tens of thousands of DIPG cells, only a few remained.

The next step: human clinical trials that could offer real hope to children battling DIPG.

We interviewed Dr. Monje about her research, her inspiration and her experience as a woman in science.

ALSF: Did you always want to be a doctor?

MM: I have wanted to be a doctor since kindergarten, inspired by the father of my best friend who was a pediatric hematologist/oncologist. I remember my mother telling me, “He takes care of sick children. It is the most important job that anyone can do.” This dream was nearly derailed in high school because of a discouraging moment in my biology class when a teacher once said to me, “it’s a rare woman who has a mind for science, sweetheart.” But, I got back on track because of a wonderful biology professor (Kate Susman) in college (Vassar).

ALSF: What challenges have you faced in your career?

MM: I have had enormous support from my family and from mentors at all stages of my training from college to the present day. I am enormously lucky and not all women in science have had that kind of support. But there have been challenges.

I do find that, throughout my career, it has been a struggle at times to be taken seriously, to finish my sentences without interruption, to have my points heard. While these moments are less frequent now that I am more senior, can point to more accomplishments and have a few grey hairs, it definitely still happens. I have four children, and during each pregnancy I noticed a prominent uptick in moments I did not feel I was perhaps taken as seriously as my male colleagues.

ALSF: How do you juggle the demands of parenthood and your amazing work in the lab?

MM: Having four children during my clinical training, postdoctoral fellowship and early faculty career was not easy, but it was absolutely do-able. I make this point because as a young trainee, many people gave me the (unsolicited) advice that one cannot have a big career in medicine or science and also have children. That at some point, I would have to choose between motherhood and science.

I ignored that advice and it has all worked out so far. It worked out, in part, because I asked for what I needed (time to pump milk at work, access to a lactation space with a door and a power outlet that was not a public restroom, meeting times that did not conflict with daycare pick-ups) and did what was a little bit taboo (routinely traveling with my nursing baby and my mother as a caregiver, while my husband was home with the other kids, when I attended conferences or scientific meetings, once giving a talk with an infant sleeping in the baby carrier strapped to my torso.) It worked out for me because I was allowed to bend and break the rules. What I would like to now advocate for is a system in which the rules are designed to support scientists and doctors during pregnancy, lactation, and parenthood. Young scientists and doctors who are new parents are busy enough without needing to figure out the basic logistics necessary to get through each day.

ALSF: What would you do if cancer was cured?

MM: If cancer was cured, and the neurological side effects of cancer therapy were also cured, I would happily focus my research entirely on the basic neurobiology of how the brain develops and how it adapts throughout life. I am endlessly fascinated by the nervous system. And I would happily administer those cures to soon-to-be healthy children in the clinic.

Dr. Monje’s work studying DIPG was recently published in the journal Nature Medicine. Read more about her work studying high-grade spinal cord tumors, here.