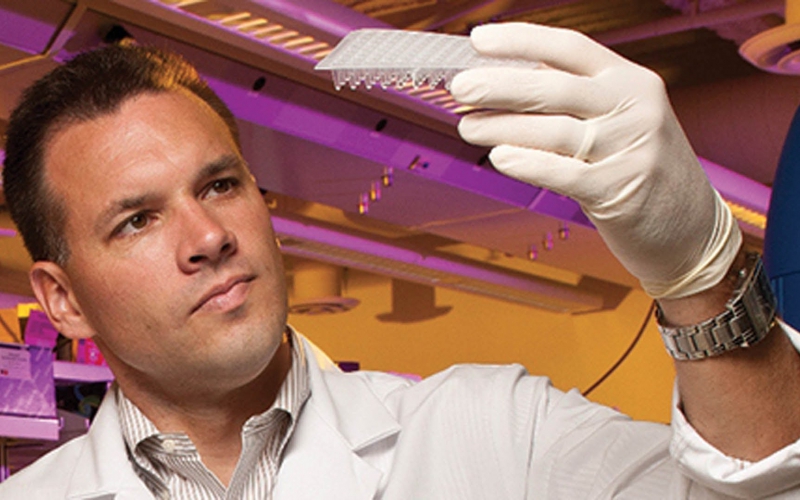

ALSF funded researchers like Dr. Todd Druley, pictured above, are closer than ever before to finding cures by studying DNA building blocks specific to childhood leukemia.

by Trish Adkins

When a child is first diagnosed with leukemia, the goal is to force the disease into remission. The treatment protocol is long and grueling—at least 2 1/2 years of chemotherapy, lumbar punctures and clinic visits. Today, children diagnosed with the most common form of pediatric leukemia—acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)—have a high cure rate. The discovery of genetic differences that can increase a child’s risk of relapse has helped some of the highest risk patients reach remission.

But, not all children with ALL reach remission. When they relapse, the second round of treatment is much more intense than the first says Dr. Todd Druley, ALSF Scientific Advisory Board Member and Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Developmental Biology and Genetics at Washington University.

Dr. Druley says the reason lies within the genetic drivers of the child’s specific type of leukemia. Better outcomes and cures will be found with continued genetic studies, innovation in technology and targeted treatments.

Understanding Leukemia

A diagnosis of leukemia is suspected after a blood test and confirmed by a bone marrow biopsy. The cells that make blood reside primarily in the bone marrow and when a child has leukemia, one of those cells becomes cancerous and overruns the other healthy cells.

While most childhood leukemia diagnoses are ALL, children are also diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), chronic lymphoblastic leukemia (CLL), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML). The acute form of the disease will grow suddenly—meaning the leukemia is spreading rapidly and outnumbering healthy cells and a child can become very sick quickly.

Managing Risk Factors

One of the early breakthroughs in the treatment of childhood leukemia was to better understand the genetic differences between adult and childhood forms of the disease. Now, researchers have deconstructed the disease even further, giving them the ability to manage the risk factors for newly diagnosed patients.

“Ten years ago, we did not appreciate the genetic differences inherent to leukemia and we thought most children had a standard risk. Now, we can see the subtypes of leukemia more precisely and provide the correct intensity of treatment,” said Dr. Druley.

This helps children with both low and high-risk leukemia. Children with lower risk factors can receive a less intense treatment and therefore minimize long term side effects (which can include cardiac damage, developmental delays and fertility issues).

If a relapse occurs, doctors now have more tools to battle the disease including CAR T cell immunotherapy, which works to harness the body’s immune system to attack the cancer cells. This therapy uses a patient’s own genetically engineered T cells (an immune cell that attacks things that are foreign to the body) to attack cancer cells that have been hiding from the immune system.

Hope in the DNA

Genetic studies have also helped doctors understand infant ALL and AML (leukemia less than 12 months of age), which has significantly lower cure rates compared to leukemia in older children. Dr. Druley’s research suggests that babies who have leukemia appear to have inherited a genetic predisposition that makes them highly susceptible to developing the disease.

Dr. Druley’s research continues to focus on determining the genetic drivers that predispose children to cancer and how to mitigate the effects of these genetic mutations and stop cancer formation. Understanding these genetic markers can also open the door to understanding how to treat other types of childhood cancer.

Scientists have discovered the same mutations in blood cells, also exist in solid tissue tumors, which helps provide critical clues into what makes a variety of childhood cancer types tick.

“Science is telling us that treating cancer by its tissue or origin ( blood, lung, brain, etc) is often less effective than treating the genetic type of the tumor, guiding us to tailor therapy in whole new and exciting way,” said Dr. Druley.

Read more about Dr. Druley’s research here.